Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

My Story

Introduction

My name is Joshua Perraton and I am from Glenties, County Donegal. My story includes my first experience with the project, a very detailed account of an unforgettable trip to Belgium, further thoughts on the project, and a poem I wrote about the German war dead. I thank you for taking the time to read my story.

I was in fifth year when my history teacher, the project co-ordinator, Mr. Gerry Moore announced the project to my history class. I was very interested in taking part in the project, and so jumped at the chance to do so. I submitted an entry essay in which I outlined my own personal interest in World War I and the reasons why I wanted to take part in the project. I was so happy when I was told I had been chosen to represent both my county and my country in such a huge project.

First Meeting - Collins Barracks, 14 February 2016

Our First Meeting took place in the Palatine Room in Collins Barracks. It was an early start to get the bus to Dublin from Donegal but it was totally worth it. The meeting was a great success for everyone involved. There were presentations made by the various leaders, including Gerry Moore who outlined the project and what it entailed as well as giving some background into World War I as a whole. It was also outlined what would happen in Belgium when we went there on the actual trip. There were ice-breakers as none of the fifteen of us doing the project had met one another previously. We hit it off very quickly and I must admit that I forged a few very strong friendships that day. After being left to meet and converse with one another, we were divided into our respective provinces and given a folder containing all of the details for the trip to Belgium. Next, we were individually interviewed by RTÉ North West Correspondant, Eileen Magnier. It was so great to have Eileen on board for the project. Finally we got a group photograph taken in the splendid courtyard of Collins Barracks and then it was time to go. I then spent a few hours exploring Dublin City before having to take another four hour bus journey home!

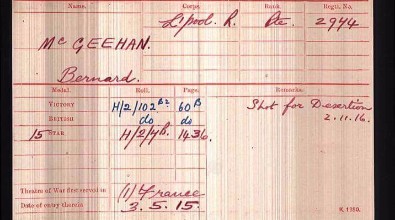

My Research

Unfortunately for me, things did not go entirely to plan while researching my soldier. I was given a contact who, as I was informed, was very passionate about World War I and also my soldier in particular. I made contact with this person, and for reasons unknown to me, she was unable or unwilling to help me. After this, I decided to search for surviving family members. I managed to find one living around Derry City, but again I never heard back from this person so was left with two failed contacts. I came across an article about my soldier on the Derry Journal's website, and emailed them to see if they could help, and once again, I never heard back. I also made contact with the Shot at Dawn Campaign Irl via a Facebook private message, but they also were unable to help. By this point, I was unsure if I would be able to find any information on Bernard. That was when I came across - by chance - a website dedicated to the remembrance of Liverpool's war dead. This website included an article about Bernard called "Shot at Dawn". It was from here I acquired the majority of my information (the article can be found here). This article was invaluable to me in creating an image of Bernard as both a man and as a soldier. Sadly, no photos of Bernard have survived but I was able to find his regiment's cap badge, his grave, and some of the houses he lived in. I contacted a member of my family who once served in the Irish Army. She did some digging in the archives for me and was able to find Bernard's medal card from 1916. This was a great thing to have. I compiled all of my information on Bernard, as well as some photographs of his homes, maps of where he served in the Great War, and other miscellaneous images which I acquired throughout my research, into a PowerPoint presentation.

The Social Aspect

After meeting for the first time in February, we, the members of the project, began to get to know one another. We created a group chat on Facebook Messenger for all members after an unsuccessful attempt to create a Whatsapp group. We all got on very well and hit it off almost immediately. The group chat was used for both business and pleasure - for sharing information and ideas, for asking for advice, and also for the usual banter while we began forging friendships. I made good friends with some of the people who did this project with me. Later, we also made a group chat on Snapchat, which gets used less frequently. It was important for us to get to know one another ahead of the project launch, to eliminate awkwardness, but more importantly, so we would all become friends with one another. In early June, we made contact with one of the German students and began making a joint group chat for both groups of students - Irish and German. The trip worked wonders for us in terms of creating and strengthening our friendships. I genuinely regard some of my fellow project members amongst my closest friends now.

The boys of Belgium. Photo taken in Schipole Airport, Amsterdam.

Project Launch - Collins Barracks, 13 May 2016

It was soon time to return to Collins Barracks for the official project launch. It was great to see everyone again. Four students - one from each of Ulster, Munster, Leinster, and Connacht, presented their PowerPoints to us. It was incredible to learn of the individual hardships each of the four men suffered in the theatre of war, and the harrowing contrasts and similarities between their stories. Gerry made another presentation, and so did David Grant from the Leuven Institute, which is where we were staying while in Belgium. The Belgium trip was outlined in its entirety, so we knew exactly what was to happen and when. We had an esteemed guest in MEP Marian Harkin, who made a powerful and emotional speech about the War and our responsibility to safeguard the future from such atrocities. Light refreshments were offered after and a group photograph was taken. I had the privilege of meeting Ms. Harkin after the presentations were all done, and I thanked her for her support and funding, as without her, this project may not have gotten off the ground. After the photos were finished, we all got a chance to chat and catch up with one another over a cup of coffee. Then it was time to leave, but it was a great day for everyone involved and a resounding success for Gerry and the rest of the My Adopted Soldier team.

Left and centre: Gerry and I at Bernard's grave in Poperinge.

Right: Visiting the execution place in Poperinge.

Travelling to Belgium

The trip to Belgium was honestly one of the most amazing experiences of my life so far. It was truly unforgettable - that is the only way I can summerise it. My fourteen fellow Irish project members were some of the sweetest, smartest, funniest, kindest, most down-to-earth people I have ever met and with them I have become very close friends even in the short time we have known one other.

After meeting at Dublin Airport on Tuesday, 20 June 2017, we set off for Brussels and later Leuven to begin our adventure, which began properly the following morning (Wednesday) with a quick tour of Leuven City followed by our first meeting with our German colleagues. We then did some ice-breakers after lunch at the Leuven Institute and a scavenger hunt in the city. Leuven is a genuinely stunning location and I would highly recommend visiting it at least once. Dinner followed and then free time within the city limits. We began to grow really close over the course of the day. We were also blessed with some very nice weather while in Belgium - temperatures soared as high as 32°C! There were some presentations in the evening and interviews with Eileen Magnier of RTÉ.

Thursday was the best day of the trip in my opinion. First off, we visited the European Parliament Building in Brussels. Talks followed from the MEPs Marian Harkin of Ireland and Gesine Meißner of Germany. We took some photographs in the European Parliament Building and then set off across Belgium to Messines where we made our first stop at the Island of Ireland Peace Park, a beautiful spot with an authentic round tower specially constructed, so we may remember both our war dead and our home country. Next up was Messines Military Cemetery, followed by the Pool of Peace. We took a minute's silence at the Pool of Peace in respect for the German soldiers who were blown to pieces in that exact spot. It was quite symbolic that new life, in the form of trees and other vegetation, should spring from a spot where so much death had occured. After the Pool of Peace we visited Wytschaete Cemetery and then Heuvellend Tourism Office where we watched a short video on the War on the Western Front called "Zero Hour". One of the most different stops of the day was the Bayernwald German Trenches, which were faithfully reconstructed to look just like the original trenches. Lastly, we travelled to to the city of Poperinge to see the death cells and execution place used by the British Army. It was at this spot that my soldier, Bernard McGeehan was executed by firing squad. It was a very emotional moment for me to stand, almost 101 years later, exactly where Bernard stood in his final moments. I was asked to present and say a few words to the group about Bernard, and then I got some photographs, and shot some footage for RTÉ's "Nationwide". Then I wrote a message for Bernard on a cross and placed it at the execution place. I got a quick look at the death cells and then we set off for a nearby hostel which was to be our base for the evening. We really bonded with one another here, spending the evening playing football, pool, chatting, and listening to music together.

Friday was our last main day. Our first stop after leaving the hostel was Poperinghe New Military Cemetery, where Bernard was actually buried after his execution. I laid on his grave the lyrics of "The Town I Loved So Well" in reference to a childhood spent in Derry City, and a Donegal and Derry GAA braid tied together to reflect his two home counties. I spoke to Eileen Magnier of RTÉ at his graveside and described his trial, death, and pardoning in 2006. After this we hit the road again, this time for a German cemetery. Visiting Vladslo was a shocking and saddening experience for me and my compatriots. To see the mass graves containing twenty men each and in poor repair was sobering. After visiting the statue of the Grieving Parents and laying flowers at their feet in remembrance, we Irish students took it upon ourselves to clear the grass and dirt off as many of the headstones as we could in the short time we had in the graveyard. It made us realise that the only difference between the Allies and the Central Powers was that the Allies won the war. After Vladslo we visited our penultimate Allied Cemetery, Poelcapelle. Inside this cemetery is the grave of John Condon, a Waterford native and possibly the youngest soldier to die in the Great War. The song "John Condon" was performed beautifully at the graveside by project members Jessica and Ciara, accompanied by David Dunlop, one of the leaders. My friend and project co-member Shane read a self-written poem at the grave of his soldier, John Sherman. Between the music and the poem, I was on the verge of tears such was the power and emotion of the performed arts in the cemetery. There was one more German cemetery to visit - Langemarck, which included an enormous mass grave in its centre containing 25,000 corpses. To see this was stark and gave a new perspective to the War from the German side. We had some free time in the Belgian city of Diksmuide in between visiting cemeteries to get some lunch. The final cemetery we visited was Tyne Cot - the largest British military cemetery in the world. There was a sense of joy enclosed within the grounds of Tyne Cot which was not felt in the other cemeteries - it was so large and full of people. We went to the city of Ieper/Ypres and visited the stunning In Flanders Fields Museum. After this we had a delicious meal at Captain Cook's restaurant in Ypres before attending the Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate. The Last Post Ceremony was incredible to witness and I would highly recommend everyone sees it at least once in their life. After the Last Post it was back to Leuven for our final night in Belgium!

Our final day was mostly spent travelling. We left Leuven at 08:30 after bidding our farewells to the German students, and then set off for Schipole Airport in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The bus journey was great fun, and the flight home was relatively short. A tearful and emotional goodbye followed at Dublin Airport and then we went our separate ways. Luke, my fellow Donegal student, and I took the bus back to Letterkenny and we were back at home in beautiful Donegal by around 22:00. I was really sad that the project was over, but also extremely happy that it had happened. I came home with no regrets, and would do it all again without question.

Cleaning grass off of the graves of German soldiers in Vladsloe.

Reflections

Not one word of an exaggeration, I can honestly say that taking part in My Adopted Soldier 2017 has changed my life in ways I could never have imagined. It has made me more confident and improved my ability to speak in front of people and to interact with others. I've made some incredible friends also, and my perspective and opinions on the First World War have changed and broadened. I think it has also expanded my world-view and political identity due to the international aspect and the historical information I have uncovered. I would not have changed a thing about the project or the trip and I can honestly say I have no regrets.

Bernard McGeehan was an amazing man with a fascinating story. It was my absolute honour to bring him back to life. I only hope others can remember and respect him the way I have, because it is the very least he deserves.

Sometimes new friends are the best friends. Photo taken in Ypres.

Eulogy for Dead Men

~ Joshua Perraton

As I kneel by their grave, I can hear

the men, screaming in deathless voices.

It is unfair.

Unjust.

Did these men deserve to die?

Did their deaths serve a purpose?

I ignore the other people, the cell phones,

even the beating heat of the sun.

I look at the grave.

I read each of the names.

Some were young. Some were old.

All were German.

Were these men my enemies?

The grave is defiled.

Grass and leaves adorn it like a parasite.

A sarcastic crown.

The least I can do is wipe it clean.

As I stand up and leave,

I can hear the dead men whispering

their thanks in the wind.

This is a poem I wrote about my thoughts on visiting the German cemetery at Vladsloe, shortly after the trip concluded.

Thank you so much for reading my archive.