About Me

My name is Maria Henehan and I am sixteen years old. I live in Sligo and go to the Ursuline College, where I am currently in Fifth Year. I found out about the project from my history teacher, Ms. Timoney, and decided to apply as I have a great interest in stories about World War One, especially as a relative of mine fought in the war and survived. I was very excited to hear that I had been chosen to take part. Doing this project and visiting the graves in Belgium was an amazing experience I will never forget, and has certainly given me a better idea of the lives and tragic deaths of soldiers from Ireland at the time.

My Research

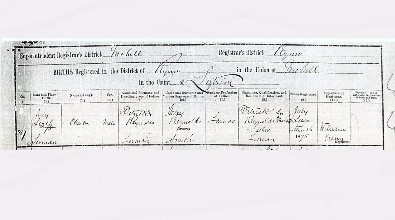

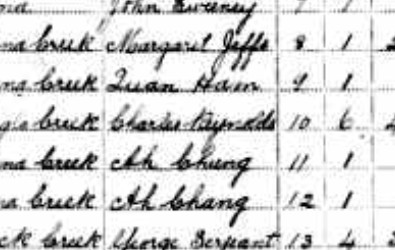

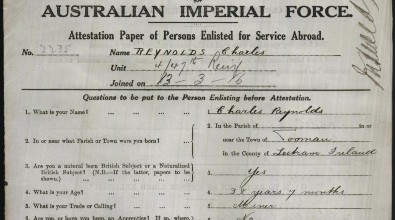

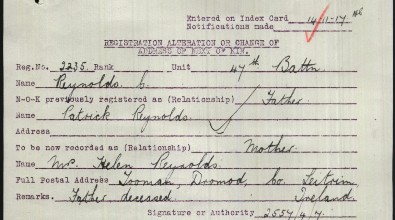

When I attended the very first meeting, after being introduced to the other students, I was given a name, address and a number: C. Reynolds, Tooman, Dromod, Co. Leitrim 2235. I did not even know his first name.

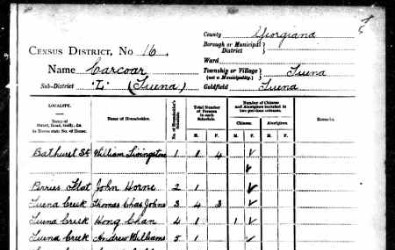

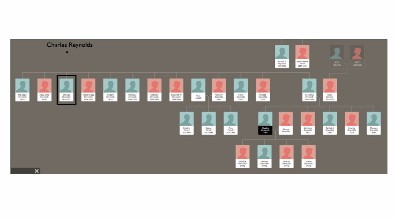

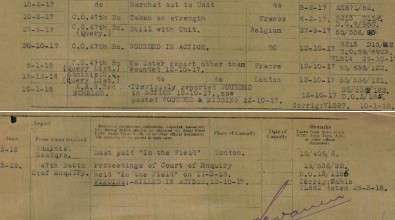

I found it hard to get information at first, as I could find no record of a C. Reynolds in the British army. I soon discovered however that my soldier had enlisted in Australia, where he was living at the time. This was a very interesting discovery for me. I discovered his name was Charles, and got in contact with relatives after months of searching.

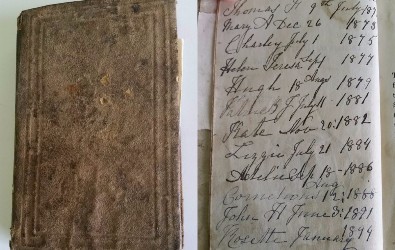

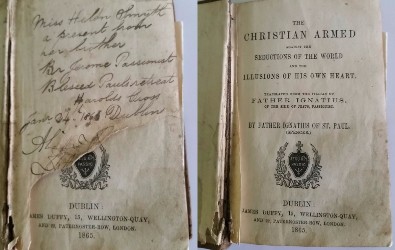

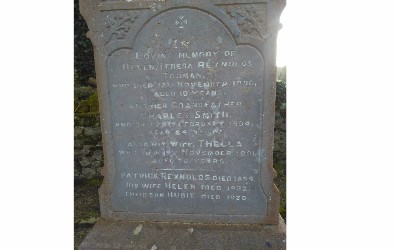

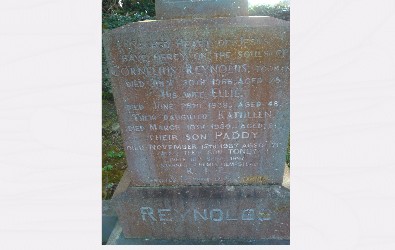

Charles relatives, grandnieces and a grandnephew in law, were a great help to me. They had artefacts and photographs from the time period, and knowledge of the family that proved invaluable.

This is a picture of Gerry Matthews, Charles Reynolds' grand nephew in-law, and I at the graves of Charles' parents and some siblings in Bornacoola, Leitrim.

Michael Reynolds, a relative of Charles, at Charles' grave. He visited the grave a few years ago.

Seeing My Soldier's Grave

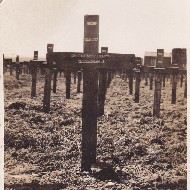

Seeing the grave of my soldier was an incredible experience. It was very emotional for me, after spending months researching him and learning all about his life and family, to finally stand at the place where his body was put to rest. I only had a few moments at Charles Reynolds' grave, but I will never forget how it felt to see his grave for the first time.

Charles Reynolds' Grave

This is a picture of me at Charles' grave for the first time, and a picture of his grave. The inscription, as requested by his mother, reads: 'O most compassionate Lord Jesus grant him eternal rest'.

The trip

Tuesday

We arrived at Dublin Airport on Tuesday evening, eager to get to our destination of Leuven in Belgium. Our flight arrived late that night and we all went to bed straight away, exhausted after a day of travelling.

Wednesday

We stayed at the Irish College, and had a walking tour of the town the next day. The German students arrived at about one o'clock on Wednesday, and we waited in the garden to greet them. We spent the day doing icebreakers and having a scavenger hunt to get to know each other better.

That evening two Irish students and two German made presentations on their soldiers.

-vklbz3.jpg)

A building in Leuven

The town hall, built in the 15th century

Thursday

On Thursday morning we had an hour-long bus ride to the EU Parliament. There we met Marian Harkin, and Gesine Meissner, the Irish and German MEPs who have helped out the project with funding.

One Irish student and one German student made presentations at the Parliament. Then we made our way to our next destination, the Island of Ireland Peace Park. We spent a few minutes at the Peace Park remembering all of the Irish soldiers who died in the First World War.

Our next stop was the Messines Military Cemetery. Here we visited the graves of Zoe and Ruari's soldiers.

Then we came to the Pool of Peace. The Pool Of Peace is a man-made pool that as created when a massive mine explosion under German trenches was carried out.

Monuments to different Irish divisions at the Island of Ireland Peace Park

The Pool of Peace

Wytschaete Cemetery was our next stop. Here Mary visited the grave of her soldier and told us a little about his life.

We soon came to Bayernwald, where we visited restored German trenches that gave us an idea of how terrible and cramped life was for the German soldiers in the trenches.

Our last stop that day was to a Death Cells & Execution Spot in Poperinge. This was where the British army would execute deserters or 'cowards'. The condemned soldiers would be tied to a pole and shot at dawn by their own comrades. Joshua told us the story of his soldier, an autistic young man who ran away and was accused of cowardice.

Wytschaete Cemetery

German trench at Bayerwald

Execution pole in Poperinge

Friday

On Friday our first stop was to Poperinge Cemetery where Joshua, Shania and Rosie visited the graves of their soldiers.

After this we came to Vladslo Cemetery, a German graveyard. Here Nelson and Shakeé told us the story of Käthe and Peter Kollwitz, a mother and son. Peter was a young German man who was killed in the war. His mother spent many years of her life creating two statues known as the Grieving Parents. We all laid white roses at the foot of the statues and spent a few moments in silence to remember the German dead.

Our next stop was Poelcapelle Cemetery. Shane and Conor visited their soldiers' graves, and we visited the grave of John Condon, who is believed to have been the youngest Allied soldier to die in the First World War at the age of fourteen. Ciara and David Dunlop performed some music and Jessica sang the song John Condon.

Poperinge Cemetery

On of the two statues of the Grieving Parents at Vladslo Cemetery

Langemarck German Cemetery came next, where we saw the graves of German soldiers and Lisa, Laetitia and Florentine spoke about their soldiers.

After a quick stop for lunch, we visited Tyne Cot Cemetery. Here, my soldier and Aoife's were buried and Jessica, Luke, Sarah and Sophie's soldiers had a place on the memorial wall. Tyne Cot is the largest of all the cemeteries we visited, with 11,954 soldiers buried there. It was an amazing experience to finally visit Charles Reynolds' grave, and see for myself his final resting place.

Next, we came to the town of Ypres, where we visited a museum dedicated to the first world war. Ciara found her relative's name on the Menin Gate, and rested a wreath in honour of the dead along with a German student.

Mass gravestones at Langemarck German Cemetery

Tyne Cot Cemetery

The Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres

Saturday

On Saturday we said goodbye to the German students and headed to Amsterdam, where we caught a flight back to Dublin. Here, the Irish students said goodbye and went our separate ways.

The trip was an amazing experience that I will never forget and I would like to thank all involved for all of the preparation and funding that went into it!